Five questions for our government – five opportunities for conversations about the future of our national community.

(Although this post reflects a New Zealand perspective, I know that the questions posed are also relevant for other democracies where growing income inequality evidences unsustainable inequities in the way we treat ‘our people’ – the national community we presume to call ‘our country’.)

At a time when an OECD report has debunked the myth of trickle-down economics, and rated New Zealand as one of the worst performers out of 34 OECD countries in terms of improving income inequality within our national community, it seems important and timely to pose a few questions to our ‘national leadership team’ – the elected members of our parliament.

Q1.What is our purpose other than to serve our people?

PURPOSE & LEADERSHIP

“…government of the people, by the people and for the people.” – Abraham Lincoln

One could be encouraged by the level of positive commonality in the ‘statements of intention’ of New Zealand’s three major political parties:

- The National party ‘seeks a safe and prosperous New Zealand that creates opportunities for all New Zealander’s to reach their personal goals and dreams.’

- The Labour party ‘will provide all New Zealanders with the support and opportunity to achieve their potential, no matter their background.’

- And the Green party envision that ‘New Zealand is a place where people respect each other and the natural world we share. It is healthy, peaceful and richly diverse.’

You might think that these statements offer the potential for a shared (political) vision or ambition for our country, our national community, which could go something like this…

‘A peaceful, richly diverse, safe, healthy and prosperous nation of people who respect each other and the natural world they share, and enjoy the opportunity to achieve their potential, their goals and dreams, no matter their background.’

But, alas, the opportunity for a common political platform is lost in the differences that emerge in the values and policy platforms of our major political parties – telling differences in the way that each party intends to achieve their ambitions for ‘our future’. And because our democracy allows only some of our elected parliament the power to govern, the ambitions (and values) of those not in power, who represent a large section of our community, perhaps more than 50%, are unlikely to be accommodated.

And so, how could this be different?

Imagine if our parliament could adopt a shared purpose that embraced the notion of ‘selfless service to their community’ – a service that was defined with and for that community. And imagine if all of the members of parliament were included in the policy dialogue about how to manifest that shared purpose – how to achieve a common ambition (shared intention) for our national community. Imagine if the differences in party-political agendas and values were admitted as genuine opportunities to co-create new and different pathways for change. And imagine if this dialogue was intended, in the longer-term, to generate outcomes that created equitable-shared value for all of our people, our national community.

Not possible in our lifetime I hear you say? And I say why not? Why not ask the question, begin the conversation and…

Take the first step – enable knowledge sharing. Provide all members of parliament with equal access to the information assets of government departments. Increase public access to government information – embrace freedom of information as an operating value (rather than regulating entitlement), simplify information access pathways and provide timely responses to information requests from government departments.

Take the second step – foster collaborative learning. Enable the whole parliament to participate in the policy dialogue (not debate) – establish policy forums (not select committees) that are truly representative of our elected parliament – forums that openly share knowledge, agree what ‘success’ could look like, consult with the wider community and genuinely collaborate to explore opportunities for co-creating solutions that work for most of our people.

If we preference the views of some at the expense of others, how does that serve our people?

If we preference those who elected us, how does that serve our people?

Q2.Who are our people other than everyone who lives in our country?

PEOPLE & COMMUNITY

“Do you know your people, do you love them?” – Mother Teresa

Unfortunately there is evidence to suggest that the high achieving members of our community are likely to regard those who lead impoverished lives as lesser human beings. Or, in other words, most wealthy people don’t really ‘see’ the poor people. Happily, there is also evidence that this negative stereotyping or categorisation can be broken down by socialisation, the development of meaningful relationships that enable the individual humanity of people to be ‘seen’ – recognised, understood and appreciated. It is through trusted relationships that we have the opportunity to recognise the potential of each individual to make a valuable contribution, to understand their rightful place in ‘our community’ and to appreciate the difference they can bring.

The question ‘who are our people?’ not only challenges us to consider who we include in ‘our community’ and why, it also questions how we ‘see’ the members of that community – how we ‘know’ who they are. For inclusion without understanding, without empathy and goodwill, is ingenuous and uncaring. It is perhaps the worst form of exclusion – it is isolation.

New Zealand’s proportional representation system of government is quoted by some as being one of the best forms of democracy in the world. In theory it enables the membership of our parliament to reflect the diversity of our national community. But representation is filtered by political party affiliations and becomes more or less effective depending on which political parties are ‘in power’. And so, while our parliamentary community may have the opportunity to ‘see’ all of our people through the collective ‘eyes’ of its members, ideological agendas and power politics diminish the voices of difference and dissent. For those voices to be properly heard would require our parliament to operate as a collaborative community, to learn from and with each other, to embrace their own difference and diversity and so welcome the different perspectives of the total electorate community. Unfortunately, our recent experience with the ‘dirty politics’ saga reminds us that our parliament currently lacks the maturity to operate as a collegial community.

And so, how could this be different?

Imagine if the leadership of our political parties agreed to operate parliament as a community of purpose, to look for commonality of interest and to act collegially in the collective best interests of the whole New Zealand community. Imagine if the ‘ruling coalition’ could be extended to include other parties, that parliamentary decisions really reflected the balanced view of the community and not just the policy view of the ruling-coalition parties. Imagine if parliamentary debate could become a generative dialogue where the participants genuinely reflected the diverse views of the New Zealand community and the outcomes represented equitable value for that community.

‘In your dreams! Impossible!’ I hear you say. But I say why not? Why not ask the question, begin the conversation and…

Take the first step – focus on commonality not difference. Explore the opportunities for positive alignment and/or integration of party-policy outcomes rather than accentuating the differences in political values and party-centric processes – focus first on the positive outcomes we want for ‘our community’ and be open to different ways to get there.

Take the second step – foster collaborative dialogue. Host possibility conversations that listen to the voices of the whole parliamentary community – value the difference, diversity and dissent within that community as the real opportunities for progressive learning, for creating different pathways and new outcomes. See all (or at least more) of ‘our people’ by engaging the diversity that presents within a multi-party dialogue.

If we cannot ‘see’ our people, how can we know who they are?

If we do not ‘know’ our people, how can we act in their best interest?

Q3.Do we know what our people know?

POTENTIAL & LEARNING

“When you talk you are repeating what you already know, but if you listen you may learn something new” – Lao Tzu

Our electoral system, which allocates policy and legislative power to a particular political party or coalition ideology for [only] three years at a time, is seen by some as a good way of keeping our parliament continually accountable to the people. But we also know that this brief parliamentary cycle pressures the government for short-term outcomes, narrows the window for informed conversation and makes it virtually impossible to pursue a rational longer-term agenda for meaningful change.

There is not enough time to consult, to listen to the ‘common sense’ of our community; there is not enough time to share information and ideas, to engage the potential of our people; there is not enough time to consider options, make informed decisions and reflect on progress; there is not enough time…to learn.

And when governments enter power and focus on their policy agenda, their information window narrows to their policy and administrative priorities and their appetite for different perspectives is filtered through an ideological lens. The parliamentary debating chamber and the select committee meetings become ‘contested spaces’ rather than ‘thinking places’ – places for sharing information and ideas. Government departments become the government’s primary source of information and policy advice but within prioritised and ideological frames as departmental CEO’s assume accountability to their ministerial masters. Parliament’s external information flows from political party conversations with professional lobbyists, focus groups and their electorate are clearly filtered through a party-policy lens. And community advocacy groups, which continually struggle for access to authentic information, tend to be seen as problems rather than as valuable contributors to policy conversations. And thus the information and idea flows narrow and the opportunity for a more open, transparent and continuing connection with the diversity of our national community is effectively recessed until the next election.

And so, how could this be different?

How could we create more time and opportunity for learning as a community? How could we establish a more open and vibrant connection between our people and our parliament? How could we learn with and from our people?

Imagine if the parliamentary terms were extended to five years to enable a longer-term view. Perhaps this would de-pressure decision-making, allow more time for consultation, and allow more time to achieve and evaluate outcomes. Imagine if collaboration within the parliamentary community was seen as a strength rather than a weakness. Perhaps this would admit the value of difference and diversity and enhance the potential for building national community. Imagine if parliament hosted regular community forums to discuss important policy issues, open and authentic conversation that involved all political parties seeking input from ‘their people’. Perhaps this would enable the ‘common sense’ of the people to be a real factor in developing the future of our national community. And imagine if authentic advocacy groups were seen a sources of valuable information and ideas; welcomed, enabled and encouraged to participate in policy conversations. Perhaps this would enable those groups to become a valued independent source of information and ideas and influential and informed collaborators within the communities they represent – ‘our people’.

‘Idealistic and unworkable’ you may say. But I say why not? Why not ask the question, begin the conversation and…

Take the first step – encourage advocacy. Invite some key advocacy groups to participate openly in core policy formation, to become fully participating members (with equal access to government information sources) of cross-party policy forums to design important long-term policies (e.g. the poverty action and social/community housing groups as members of a housing policy forum?). Publish the forum proceedings, invite public participation, host community conversations and acknowledge contributions.

Take the second step – encourage a long-term view. Begin a community conversation by publishing a draft ten-year strategy for education, health and social assistance. Inform the strategy by hosting online conversations with independent moderators to enable focussed discussion and contributions from communities of interest; and enable relevant government departments to respond openly to moderated information requests.

If we do not welcome community advocacy how can we know what our people know?

If we care for our people why would we not share our aspirations for their future?

Q4.Do we enable our people to contribute to their future?

PARTICIPATION & CONTRIBUTION

“A nation’s greatness is measured by how it treats its weakest members” – Mahatma Ghandi

Enabling people to contribute is firstly about recognising and valuing their potential to contribute and then providing contribution opportunities – access points and pathways for people to participate in the co-creation of a shared future. In a society where the value of education is associated with ’employment’, where the value of arts and culture is increasingly assessed through a ‘creative industry’ lens, it is not surprising that human potential tends to be measured, and therefore valued, in terms of its economic contribution. Inevitably this leads to a ‘paid work’ view of the world where ’employed’ people are valued over ‘unemployed people’, where failing to be employed attracts value-penalties in terms of very low incomes and often unhelpful ‘participation requirements’. Unfortunately this seems to reflect a view that unemployment is a participation-application failure (you could work if you really wanted to) rather than a participation-opportunity failure (there simply aren’t enough suitable jobs) and, therefore, the fault of the unemployed. And these penalties persist in spite of the fact that our national economy is managed on expected levels of unemployment, that labour-engagement gaps are a natural consequence of supply and demand tensions in market-based economies.

This picture is further complicated by the large number of unpaid (but arguably ’employed’) people in our community whose potential to contribute cannot be easily measured in economic terms. In a society that has learned to preference paid work, how do we value the unpaid contributions of our people? In our national community, where there will never be enough ‘paid work’ to engage those who are eligible to participate, how do we value the contribution of the those who are unpaid – our young people, our parents and care givers, our volunteers and those that cannot perform paid work for whatever reason – in fact the majority of our people? How do we value contributions that cannot be measured in terms of their monetary value – contributions that are vital to the proper functioning of our community? And contributions without which our ‘paid-work’ economy would not function?

If we cannot assess the value of unpaid work, how do we make sure that the potential for contribution by our unpaid workforce is recognised and valued by those who frame the socio-economic future of our country – our elected parliament?.

And so, how could this be different?

How could we value the contribution of all of our people in a way that recognised their potential, acknowledged the importance of their role in our community and encouraged their participation?

Imagine if the entire social assistance (benefits) regime was reinvented with the purpose of ensuring a ‘fair income’ for all of our people irrespective of their paid or unpaid work status. Imagine if that reform recognised the value of our children and adjusted benefit values to reflect the real costs of sustaining their wellbeing. Imagine if we could make education valued in its own right and create new pathways that would see all of our young people graduating from high school. Imagine if our education system was restructured to create undergraduate colleges where participation was free and where course offerings increased access options and learning pathways for high school graduates. Imagine if health care was free for our children and young people (to under-graduate age). Imagine if we as a country had the courage to progressively invest in such initiatives, to appreciate their long-term nature, to be innovative in their design and implementation. Imagine if we trusted our people to engage positively and productively with such a framework and to become full and active participants in our community over time.

‘Unrealistic’, I hear you say. ‘Such arrangements would be unaffordable and open to abuse’ I hear you complain. But I say why not try? Why not ask the question, begin the conversation and…

Take the first step…encourage real participation. Anchor and align unemployment, sickness and single-parent benefit payments around the current national superannuation levels and review the access requirements to ensure they are equitable and focussed on encouraging meaningful participation in our community.

Take the second step…put our people first. Establish a parliamentary review (involving all political parties) of the social assistance regime and associated tax breaks and incentives with a view to establishing an accessible, transparent and equitable system that would enable all of our ‘unpaid’ and ‘unemployed’ people to access a ‘fair income’.

If we do not value our people how can we expect them to value themselves?

If we do not educate our people how can we expect them to contribute to their future?

Q5.Are we co-creating a sustainable future for all?

WELLBEING & SUSTAINABILITY

“The greatest country, the richest country is not that which has the most capitalists, monopolists, immense grabbings, vast fortunes, with its sad, sad soil of extreme, degrading, damning poverty, but the land in which there are the most homesteads, freeholds – where wealth does not show such contrasts high and low, where all men have enough – a modest living – and no man is made possessor beyond the sane and beautiful necessities” – Walt Whitman

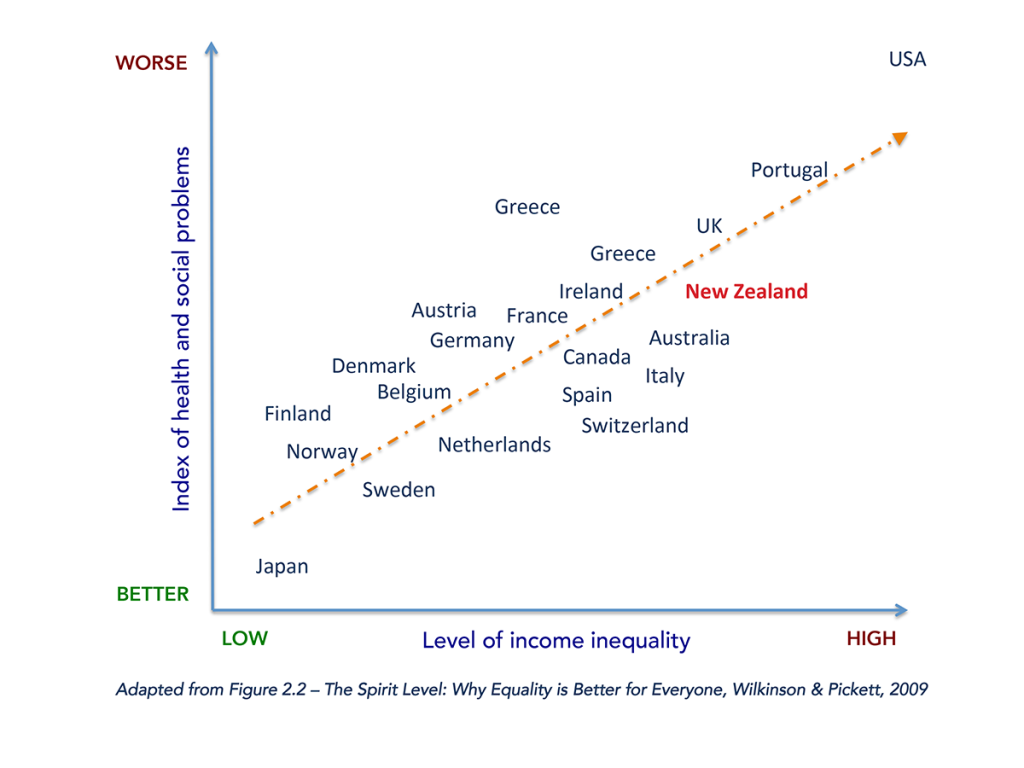

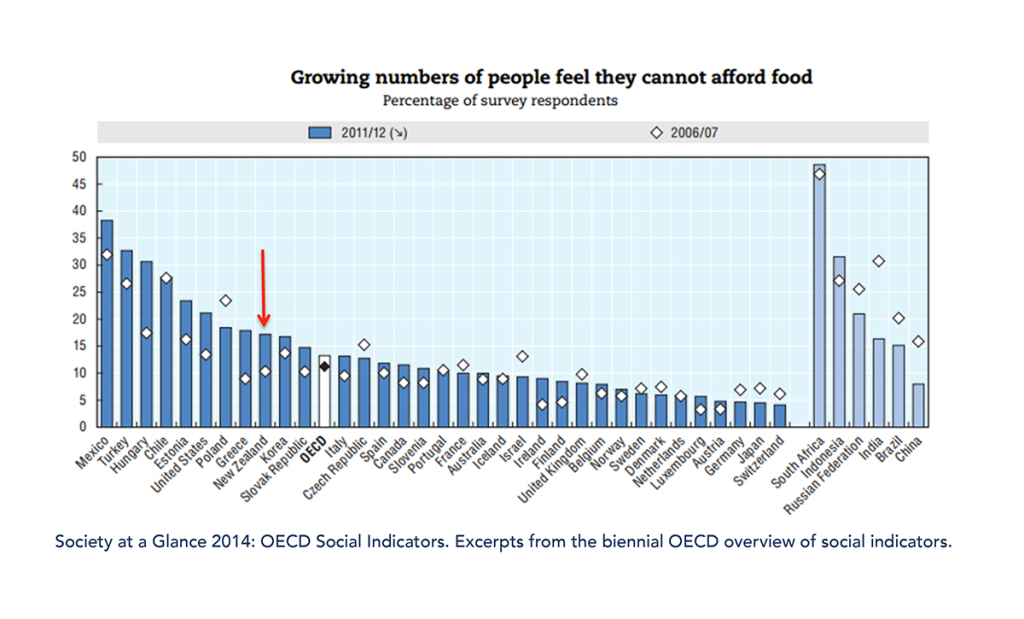

The recent OECD report on income inequality makes it very clear that not only does New Zealand have a major income-inequality problem; it has one of the fastest rates of inequality growth of the 34 OECD countries included in the report.

This rapidly increasing gap between the rich and poor is sadly evident in our appalling child poverty statistics (one in four children living below the poverty line) with low incomes recognised as one of the main causes. And as intergenerational poverty continues to grow, the ability of the poor to connect with the economy as ‘paid workers’, to access a ‘fair income’, will become increasingly difficult due to underfunded and penalty-framed social assistance programs, and restricted access for our poor people to appropriate education and health programs (for example).

How can those who argue in favour of growing the economy as the only way to resolve poverty continue to ignore the immediate plight of our poorest people? In a relatively rich country, which can produce a surplus of nourishing food to provision other countries, how can it be possible for our own people to be hungry?’

There can be little doubt that ‘our people’ do not enjoy an equitable share in the wealth of their country. The admirable party-political aspirations for all of our people to have ‘equal citizenship and equal opportunity’ and be able ‘to achieve their potential no matter their background’, remain very distant visions of the future for many. Even to meet the minimum standards set down in the United Nations Declaration on Human Rights (Article 25) would require us to share our national wealth in ways that enabled all of our people to access the food, shelter, medicine and social assistance they need to keep them safe and well.

As the OECD report comments, the widening gap between the rich and the poor, which has negative socio-economic consequences for everyone in the country, should be reduced by implementing appropriate tax and benefit reforms that help to provide a fair income for all – an income that makes it possible for all of our people to participate as equal citizens in their society.

And so, how could this be different?

How could we move towards creating a society free of disabling levels of poverty? How could we begin to lift our poorest people out of their poverty now?

Imagine if we believed in the ‘inherent goodness’ all of our people, irrespective of their background and current situation, and trusted that over time we would all benefit from releasing our people from poverty. Imagine if the minimum wage was replaced by a mandated and indexed living wage designed to enable an individual to access the essential requirements for food, shelter and medicine. Imagine if unemployment, sickness and single parent benefits were increased to the level of national superannuation, similarly wage (not CPI) indexed, and available to supplement part-time employment. Imagine if taxation rates, incentives and exemptions, along with other social assistance programs, were designed as an integrated system to provide a ‘living family income’. Imagine if we had the courage to launch and sustain this program for several decades to enable the progressive eradication of intergenerational poverty.

‘Such arrangements would be unsustainable! They would destroy jobs, act as a disincentive for many people to participate in our economy and make us internationally uncompetitive’ may be your reaction to such proposals. But I say why not seriously explore the options? Why not ask the question, begin the conversation and…

Take the first step – frame a future without poverty. Paint a picture of a future without poverty. Show how we could all benefit from releasing our people from poverty. Provide an alternative view of the future where there is no child poverty and the income gap between the rich and poor is the lowest amongst the OECD countries

Take the second step – make a plan. Create a multi-party government plan to ‘make poverty history’. Collaborate with colleagues, relevant experts and community groups to design and implement long-term policies to progressively increase the incomes of our poor and disadvantaged people and to improve their access to food, shelter, education and health care. Set realistic and long-term public goals, monitor progress and create learning-feedback loops to inform future change.

If we cannot imagine a future without poverty, how can we plan for one?

If we do not plan for a future without poverty, how can we hope for one?

These five questions are derived from The Congruence Framework, a framework designed to enable and encourage individual, organisational and community congruence – the harmonious alignment of people with and within their communities.

The question ‘Is this my community?‘ challenges us to examine the realities of our engagement with our personal, organisational and national communities and to explore the nature of the relationships that enable or disable our ‘belonging’. We cannot always choose to ‘leave‘ the communities where we are not welcome, which is why many people ‘hibernate‘ and hope for change. And all too few of us seem to have the capacity to influence significant change within our communities – or do we?

“Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world. Indeed, its the only thing that ever has.” – Margaret Mead

Leave A Comment