Five questions for the people who are the political voice of our poorest children.

It is an opportune time as New Zealanders prepare to vote in their country’s parliamentary elections to reflect on the politics of poverty and how we think about our collective responsibility to care for some of the most vulnerable members of our community –

more than 250,000 New Zealand children, about 25% of our child population, who live below the poverty line.

Not only is this an alarming statistic for a country with a relatively healthy economy, but even more alarming is the rate at which child poverty has increased in New Zealand over the last two decades, and the fact that it now seems to be entrenched.

This is our community, these are our children; their suffering will also be our suffering.

It is probably no coincidence that this entrenchment occurs at a time when many New Zealanders are becoming increasingly resistant to the imposition of a more progressive tax regime (which would mean relatively higher taxes for the wealthy), and less concerned about the widening gap between the rich and the poor people in our community. These entrenched positions form a barrier to the enactment of wealth sharing policies that would assist low-income families. But perhaps this is not so surprising given that our domestic fiscal policies, aligned with those of the other major Western democracies, fail to address the well-known flaws in the international monetary systems that influence our economy to widen the wealth gap. (This is the subject of an earlier post titled Money, money, money, it’s a rich man’s game.)

We can argue about the child poverty measures (a relative mix of income poverty and hardship), disagree about the causes (largely income related), shake our heads at the ethnicity of the problem (about 50% Māori and Pacific children) and look to blame someone else (typically the parents and/or their communities). But that won’t change the fact that we, as a community, have a serious problem that can only be resolved if there is a political will – and therefore a community will – to address it. And therein lies the real issue – do we as a community really care?

Do we really care about the many children in our community whose circumstances are not of their own making and who go without nutritious food; are often wet and cold because they lack proper clothing; wear worn-out shoes or go barefoot; live in a cold, damp house; sleep in a shared bed; suffer third-world levels of rheumatic fever; arrive at school unable and unprepared to learn; can’t afford the gear to play sport; are unable to invite friends to play or stay over; miss out on birthday and Christmas presents; and rarely experience life outside their immediate community?

Obviously these children are severely disadvantaged in terms of living their true potential as fellow human beings and citizens of this country. And that is a tragedy that should distress our community right now and will certainly haunt us into the future.

Much of the research points to income poverty as the root cause of child poverty and the significant causal factor in the wellbeing issues associated with this poverty. We may agree that only a government willing to enact meaningful long-term policy can address the root causes of income poverty. But then we must also agree that it is the New Zealand voter community that shoulders the primary responsibility and the accountability for enabling that to happen. Although there are numerous community-based organisations working hard to change public attitudes and alleviate the impacts of child poverty, they will struggle to effect major change without the political support of the wider community.

Surely we each have a responsibility to enable the possibility of a different future for these children – to be aware of the facts, to acknowledge the primary causes, to understand the opportunities for positive change and to endeavour to make those changes happen?

We can only hope to make a difference for the children who live in poverty if we can see them as our children, if we truly believe in their potential to be valued members of our community and in their sacred entitlement to be rightful citizens of their country.

The political voice of New Zealand’s one million children, who make up about 20+% of the New Zealand population, is filtered through the adult population, approximately 2.5 million citizens (based on past experience) who are likely to cast an electoral vote. And many of these voters may not be parents or people with any real experience of poverty. So, how can we seek to influence the advocacy of these voters in favour of a better deal for our impoverished children?

We could begin by talking openly about child poverty within our own communities and with those who are standing for political office. We could use the following set of questions to frame our conversations in a way that challenges the thinking and motivations of our friends and neighbours, and questions the assumptions and underlying value systems of our politicians.

Do we dream of a joyful future for the people of our country?

‘But I, being poor, have only my dreams; I have spread my dreams under your feet; Tread softly because you tread on my dreams.’ – William Butler Yeats

• What is our ambition for the longer-term future of New Zealand?

• Is it an ambition that could and should be shared by all New Zealanders?

• Does it envision New Zealand as a place for all of its peoples?

• Does it expect a better future for our children living below the poverty line?

Do we see New Zealand as a community of our people?

‘Do you know your people, do you love them?’ – Mother Teresa

• How do we define our New Zealand community – who are ‘our people’?

• How do we know our people, how do we care about them?

• Does our community include the children who live in poverty?

• How do we know them? How do we care about them?

Do we listen carefully to the many voices of our community?

‘There is one principle that can keep a man in everlasting ignorance. That is contempt prior to investigation.’ – Herbert Spencer

• Do we ‘know’ about child poverty in New Zealand?

• Do we know what our friends and community leaders think about child poverty?

• Do we understand the probable causes and potential longer-term impacts of child poverty?

• What should we do as a community to significantly reduce child poverty?

Do we make a positive difference for our community?

‘Each of us is a unique strand in the intricate web of life and here to make a contribution.’ – Deepak Chopra

• How do we contribute to the creation of valuable outcomes for our community?

• Is our contribution consistent with our ambition for the future of our country?

• Does our contribution reflect the truth of who we are? Is it the best that we can offer?

• How does our contribution make a difference for the children who live in poverty?

Are we concerned for the collective wellbeing of our community?

‘The part can never be well unless the whole is well.’ – Plato

• Can the people of our community access the resources they need to be well?

• How do we care about the (physical, mental, social and spiritual) wellbeing of our community?

• How do we share our ‘gifts’ with our community?

• How can we help our impoverished children to be well?

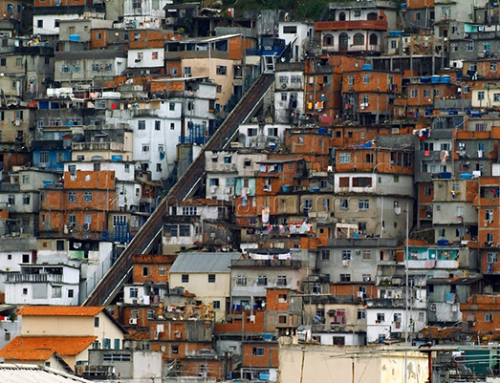

Of course these questions are also for us, to challenge our own views and to encourage us to think more about child poverty and consider becoming an active advocate for change. And they are not just questions for New Zealanders. Child poverty is a frightening statistic in many countries (e.g. The United States, Australia, Canada, The United Kingdom and Mediterranean Europe) where the income disparity between rich and poor continues to increase and, as a consequence, our children continue to suffer the inequalities of a world they did not create.

‘There is no trust more sacred than the one the world holds with children. There is no duty more important than ensuring that their rights are respected, that their welfare is protected, that their lives are free from fear and want and that they can grow up in peace.’ – Kofi Annan

Footnote: These five questions also reference the five dimensions of The Congruence Framework, a way of thinking about our organisations, our communities and ourselves that has the potential to influence the ‘harmonious alignment of people within their communities’. You are welcome to add your voice to this conversation about child poverty.

Books referenced in this post: